Learning More by Doing Less

Monday 20 May 2024

Recently, I decided to allocate some time to giving some thought into my future career path - something I'd been meaning to do for a while. During this period, I found a lot of useful resources from an organization called 80000 hours. The idea behind 80000 hours is that we have approximately 80000 hours in our career to contribute the most 'good' for society as possible, and their goal is to help people figure out how best to utilize these hours. If you're intrigued by the idea of using your career for 'good', it's something I'd definitely recommend checking out.

Anyway, one resource that stood out, suggested by 80000 hours, was a free online course called Learning to Learn facilitated by Professor Barbara Oakley. This course, available for free on Coursera, is also the most viewed online course in the world. Intrigued, I decided to try out this course a couple of weeks ago. Now, as I near the end of the course, I thought I'd share some key takeaways that I've learned so far - the central theme being 'how to learn more by doing less'.

Something I really enjoyed about this course was its perspective on what it means to learn. For the longest time, I used to have a very arcane, one-dimensional view of learning, viewing it merely as a means to an end. In the classroom, you learn in order to pass a test. When you start to work, you learn in order to perform your job effectively. However, this course extends the concept of learning beyond the process of absorbing and internalizing new information. It goes further to include situations where there's no one there to teach you, no textbook, no Google-able answer. It's in these situations where all you have is yourself, your thoughts, past knowledge, and experiences, and it's up to you to put together the pieces to come up with new insights, discoveries or pieces of art. Because of this, I like to think of the process of learning as being split into two stages - 'acquisition' and 'innovation'.

The two stages of learning

The first stage of learning, 'acquisition', is likely what comes to mind when you think about learning. This stage is about intensive focus, where you might spend hours, days, or even weeks mastering a specific topic, often for school or work. It's what's known as the 'focused mode' of thinking, demanding a linear approach with prerequisites fulfilled before advancing. Acquisition lays the groundwork, providing the necessary fundamentals to bring your own creativity to a subject. Some may find satisfaction in this stage alone, especially if their goals are confined to grades, job competence, or merely absorbing knowledge.

But learning doesn't stop at acquisition; it naturally evolves into the second stage, 'innovation'. Far from being a rare or elite skill, innovation is something we all engage in daily. It's the 'diffuse mode' of thinking, where connections are made between what you've learned and your own life experiences, including in seemingly unrelated fields. It's the stage where problem-solving and creativity come into play, where the raw material of knowledge is molded into something uniquely your own. Whether in our work, hobbies, or daily decisions, this form of learning is integral to how we navigate and make sense of the world.

'Acquisition'

Looking back at my time in high school and university, I realize I was a terrible learner. That's not to say I got bad grades; in fact, quite the opposite. But reflecting on my approach to getting those grades, I'm not sure I retained much at all. My strategy throughout school involved a comfortable rhythm of waiting until the week before a test to begin studying. I would then attempt to cram all the required content into two or three all-nighters. In my mind, this was the best approach, allowing me to invest just a few days of intensive learning rather than an entire term or semester. Surprisingly, this strategy often worked well, with all the information fresh in my memory for the test. But if I were to take those same tests today, I'm confident I would fail every one of them.

The acquisition stage of learning involves absorbing the basic building blocks that you can later build upon. To reach this stage effectively, these building blocks must become ingrained in you, stored in your long-term memory. If you're trying to 'learn' something without committing it to memory as a tool for future use, you're really just wasting your time. Reflecting on my high school and university days, I see now that those long nights spent cramming before a test were in the end a waste of time. I can't help but to think about the many hundreds or perhaps even thousands of hours I poured into last-minute study sessions, and I have nothing to show for it now. But as I look back, I ask myself: Was there a better way? Could I have achieved the best of both worlds, maintaining my good grades while crafting robust tools I'd be able to utilize today?

Something Barbara consistently emphasizes throughout the course is the importance of spaced repetition, which contradicts the last-minute cramming many of us are used to. It’s easy to assume that spaced repetition, because it spreads study over more days, equates to more study time. However, a study conducted by the University of California's psychology department in 2009 found otherwise.

In the study, they compared two groups of students preparing for different tests. One group used the 'spacing' technique, studying in short increments over several days, while the other group relied on 'massing', cramming all study materials right before the test. The total study time for both groups ended up nearly the same. Despite this, the spacing group consistently outperformed the massing group by 31%-36%.

But what's intriguing about these findings isn't just this clear advantage of spacing over massing; it's the perception participants had of their own learning. Despite the clear superiority of spacing, on average, participants predicted the massing group would do 14% better, revealing a fascinating disconnect that reveals our misconceptions about learning.

But why do we have this intuition that cramming is a superior strategy? The study suggests that this is because cramming feels more productive in the moment. During a cramming session, we're able to recall information more fluently, leading us to believe that we're learning more effectively. However, this sense of learning is deceptive, with the true reason for this stemming from our superior ability to retrieve recent information from our short-term memory. And because of the failure in our schooling system that revolves around test taking that rewards short-term memory recall, it's easy for us to fall into the cycle of using cramming strategies to meet our immediate goals of passing these tests. And, naturally, once we find something that works, we're unlikely to experiment with other strategies for learning. Though cramming may help us scrape by in these tests, the knowledge evaporates soon after, leaving us with many hours wasted with nothing to show for it except for a number or letter on a piece of paper.

It's important to remember why we learn. The true purpose of learning is to be able to build and acquire tools of knowledge that we'll be able to use some day in the future, whether that be to help us get work done, or to build upon for making creative insights or discoveries. So when it comes to studying strategies, on one hand there's the admittedly convenient method of cramming that will help you to the extent of passing tests, and on the other hand there's the method of spacing out your learning over time, forging tools that you'll be able to use for the rest of your life. Take your pick.

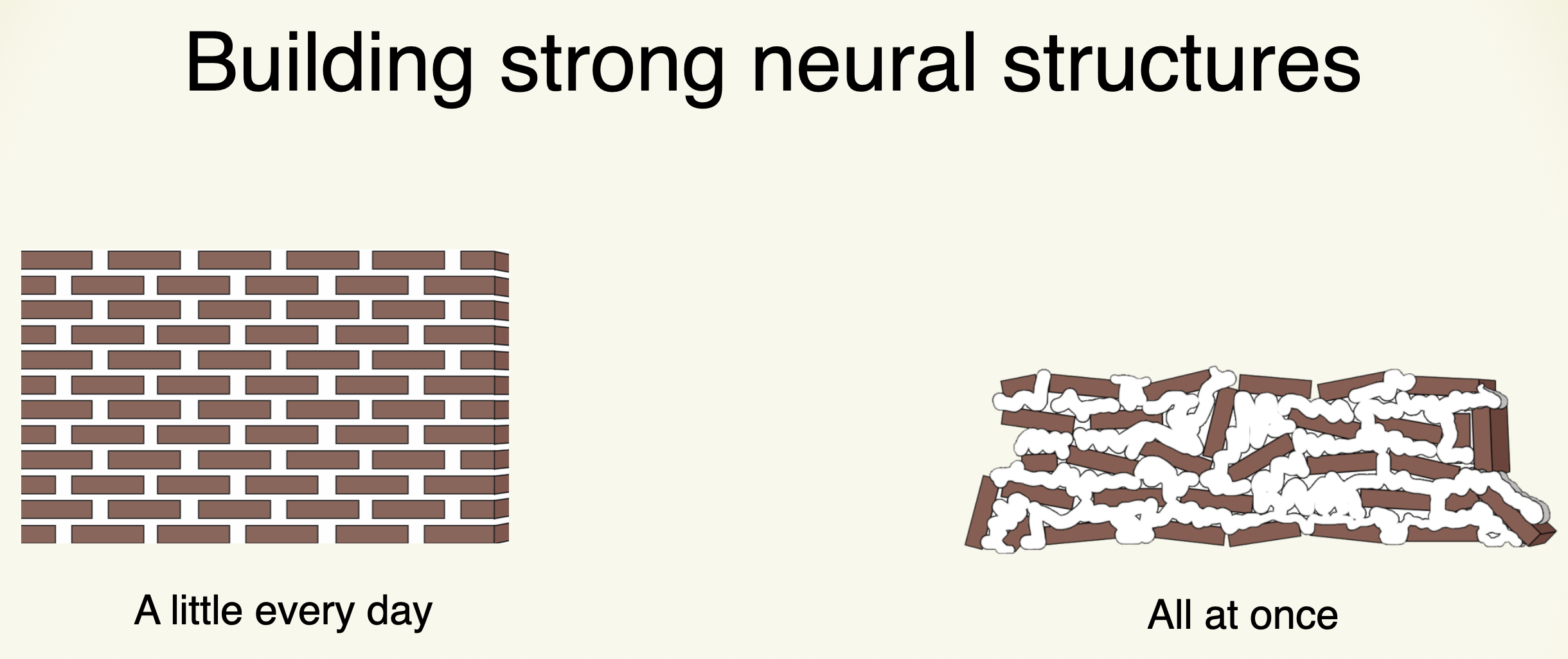

There is also a neurological argument for spaced learning. I was tossing between including it in this blog, so I'll instead give a brief summary. Anytime you start to learn something new, whether it's a new exercise at the gym or a new math formula, your brain creates a new sequence or circuit of neurons for this task. However, the connection between these neurons is weak at the start, and the only way to strengthen it is to have them fire together repeatedly. The caveat is that neurons have a refractory period, during which they are unable to fire again, sort of like a cooldown. Therefore, you have to wait for the refractory period to pass before you can activate these neurons again and strengthen the connection. This what spaced learning allows you to do. Being someone who failed their year 10 biology, please take all this with a grain of salt. If you are interested in the topic, you can learn more about it here.

'Innovation'

Have you ever had a problem you've been stuck on only to realize the answer several hours later when you're doing something completely unrelated? Or have you ever noticed your mind racing while taking a shower or trying to fall asleep? These are all examples of your mind's diffuse mode of thinking taking over.

I like to think of our mind being like a library with each book representing some piece of knowledge or skill we've learned during the acquisition stage. When we're in our normal mode of thinking (focused mode), we have go-to routes in our mind's library based on the task at hand. For example, if I run into a problem while writing a computer program, I won't be looking for answers in the 'cooking' section of my mind's library. Instead I'll probably be in the 'programming' section, staying there until I either find what I'm looking for or get tired and give up on the problem. This line of thinking works for most of our everyday problems. However, sometimes the answer to a problem does indeed lie in an unexpected section. Maybe all we needed was to look in the 'cooking' section after all. This is where the diffuse mode comes in.

If the focused mode of thinking is where you have full control over which areas of your mind library to browse, the diffuse mode is the complete opposite. When you relinquish control of your mind, it starts to wander sporadically, pulling books off the shelves at random and trying to relate them to each other. While such thoughts are usually trivial (think of your average shower thought), this random process occasionally stumbles upon a stroke of genius, allowing you to make a connection related to your problem that you never would've otherwise considered.

We can now see the connection between the acquisition and innovation stages. By building your library of tools in the acquisition stage, when you do enter the diffuse mode, you have a better chance of stumbling upon useful connections and insights. The more diverse and well-stocked your mental library is, the greater the potential for innovative ideas and creative solutions to emerge from seemingly unrelated pieces of knowledge. While this is good and all, does this mean innovation can only happen at random? Or are there things we can do to increase our use of the diffuse mode to harness its full potential?

The best way to activate the diffuse mode is by simply 'doing less'. This mode arises whenever you're in a relaxing or flow state. Here's a quick exercise you can try now if you like: close your eyes and focus on your breath for two minutes, trying to keep an empty mind. Unless you're an experienced meditator, you'll notice your mind inevitably starting to flood with thoughts.

The reason why such a mode of thinking is so rarely accessed is because of the many distractions and stimuli that fill our daily lives. There is always something to grab our attention, demanding the use of our focused mode of thinking. It is up to us to put ourselves in an environment where these distractions are limited, allowing the mind to run free. For me, this environment is the gym. I have had many answers suddenly come to me while resting between sets. But this only works if you get rid of those distractions—using that rest time to scroll through Instagram defeats the whole purpose. The bottom line is that it's really important to step back from your work or studying from time to time and transition into an environment that lets your mind do its work, whether that's going for a walk or run, a bike ride, or simply having a relaxing sit outside in nature.

There's a famous example of Thomas Edison that really illustrates this concept. Whenever Edison faced a difficult problem he didn't know how to solve, he would hold two metal ball bearings, sit on his chair, dangle his hand with the balls to the side, and try to drift off to sleep. As his consciousness started to fade and his grip would falter, the balls would fall and hit the floor, waking him up. This technique allowed his mind to wander freely and often led to moments of inspiration upon waking. Like Edison, we too can build such habits when we face difficult problems, saving us countless hours of banging our heads against the wall.

Closing Thoughts

I find it fascinating that the diffuse mode—something so powerful and readily accessible—is so rarely utilized. I suppose it makes sense; with the evolution of technology providing us with ever-increasing distractions, we find it challenging to access this mode. It makes me wonder about our early ancestors. Without today's distractions, perhaps their minds operated predominantly in a diffuse state, switching to focused thinking only when necessary. Maybe innovation was more commonplace for them, allowing them to create and evolve into what we are today.

So, have I convinced you to do less yet? Sometimes, being the hardest worker isn't always the most effective solution. Using tools like the Pomodoro timer can serve as a helpful reminder to take regular breaks, step back from distractions, and let your mind work passively in the background. By doing so, you might just discover a wellspring of untapped creativity and problem-solving potential waiting to be harnessed.